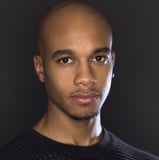

Black Boy Out of Time is the debut memoir from Hari Ziyad, who is, among other things: editor in chief of Racebaitr, a 2021 Lambda Literary Fellow, and a prolific essayist. In a word, it is exquisite.

Central to the memoir is the concept of abolition, which refers to "a political vision with the goal of eliminating imprisonment, policing, and surveillance and creating lasting alternatives to punishment and imprisonment," per Critical Resistance. In practice, it looks a lot like living in actual community with one another: a true embrace of our perceived other beyond institutions that would sooner put people in cages and out of public view than address social problems like houselessness, inadequate healthcare, and unemployment, as trumpeted by abolitionist icon Angela Davis. According to Ziyad: "It all comes back to the work that we're doing to get free."

Ziyad writes with a clarity and a strength beyond any memoir in recent memory, interweaving writing on abolition and carcerality with a stirring series of letters to their younger self as part of their inner-child work. One of 19 children in a blended family, Ziyad was born to a Hindu Hare Krishna mother and a Muslim father in Cleveland, OH. They grew up Black, queer, and - like too many racialized kids are made to - achingly fast. But in their memoir, Ziyad dials back the clock and turns inward. Peeling away the restraints, they reveal a wealth of truths around the necessity of Black liberation to the Black child and to the adult they will variably become if given the grace to grow freely.

Carceral logic is so pervasive that the work of abolition goes beyond dismantling brick-and-mortar prisons and precincts that enact harm and deep into the psyche, which becomes a site of reproducing carceral logic until we consciously unlearn to.

With patience, Ziyad lays bare just how harmful the carceral state is to Black people and how intrinsic punitive thinking can be to how we understand our outer and even inner lives. Carceral logic is so pervasive that the work of abolition goes beyond dismantling brick-and-mortar prisons and precincts that enact harm and deep into the psyche, which becomes a site of reproducing carceral logic until we consciously unlearn to. Liberation, then, is inner work as much as it's outer work. Like a social archeologist, Ziyad looks to unearth their true self - the inner child - that lives underneath binary thinking and what they coin as misafropedia, or "the anti-Black disdain for children and childhood that Black youth experience." They encounter sites of trauma and come away with nuance and new meaning, tending to their inner child with the care of a loving parent. "I want to offer colonized Black people - and myself in particular - a type of roadmap for reclaiming the childhoods we sacrificed," Ziyad writes, "or that were forsaken for us because of misafropedia."

The joy of Black Boy Out of Time is in the unconditional love it emanates for all Black people and how it attends to the experiences of Black kids. It's in its utter dedication to freer, more daring Black futures; in its imagination. It's in the calm and the wisdom of its author, who is the kind of cultural critic and champion of Black liberation that our political moment yearns for. Hailed as "Black-loving art that is both shotgun and balm" by Darnell L. Moore, Black Boy Out of Time is just profoundly great, to the point that the best this reviewer can do is to ask you to read it and know it for yourself.

In February, I sat down one-on-one with Ziyad - then one-on-one plus a live "studio" audience (via Google Hangouts) as part of a speaker series at Group Nine Media - to talk about Black Boy Out of Time and the healing work of abolition in action.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

0 Commentaires